Better HALs: First Look

Embedded Rust provides a unique opportunity for us – as embedded systems designers – to design safer, more robust, and highly adaptable Hardware Abstraction Layers (HALs).

Many Embedded Rust HAL projects exist and are actively worked on, I’ve contributed to my fair share of them in the past years, but during this time I was always left yearning for more. Yearning for greater invariance, stability, and static analysis.

So that’s what I’ve set out to do, design a system, process, or guideline for designing HALs that fully leverage Rust’s capabilities.

To explore some of my ideas, and give a go at laying out this “prototype” HAL, (we can call it proto-hal) let’s design a HAL component for a peripheral from the ground up.

I am doing some work with the G4 that would benefit from accelerated trigonometric functions, so let’s create an interface for the CORDIC co-processor.

Understanding the Peripheral

The first step is to look at any relevant documentation on the peripheral, to fully understand the scope of its operation.

The G4 reference manual RM0440 and CORDIC application note AN5325 should be useful.

Let’s see what it can do.

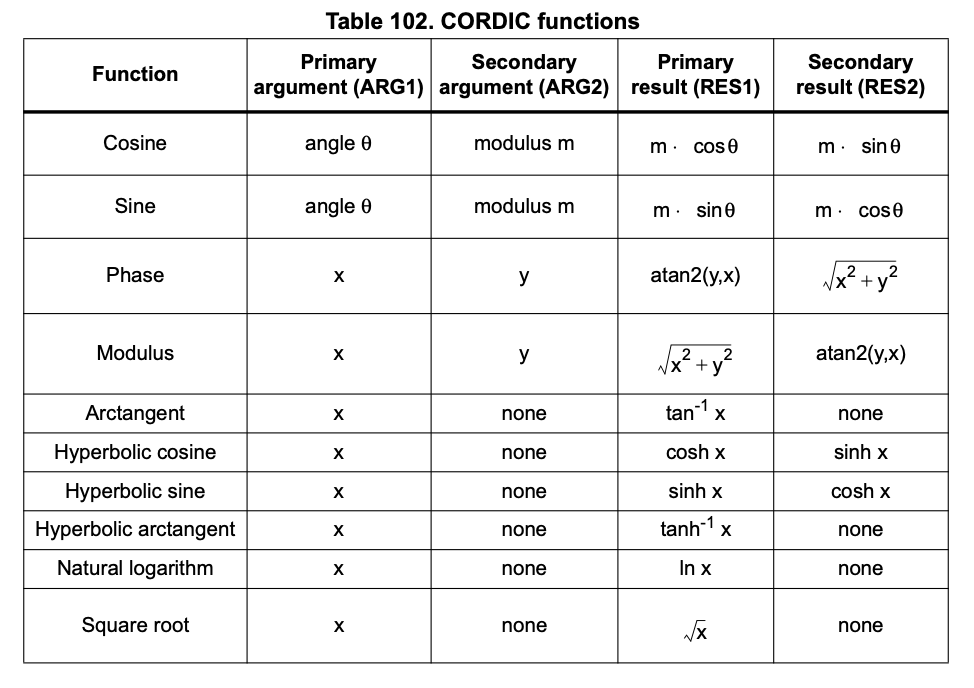

$RM0440 17.3.2

This is the list of available functions. It seems they have varying numbers of arguments and results.

Neat, to see how we actually program this thing, let’s look at the register map:

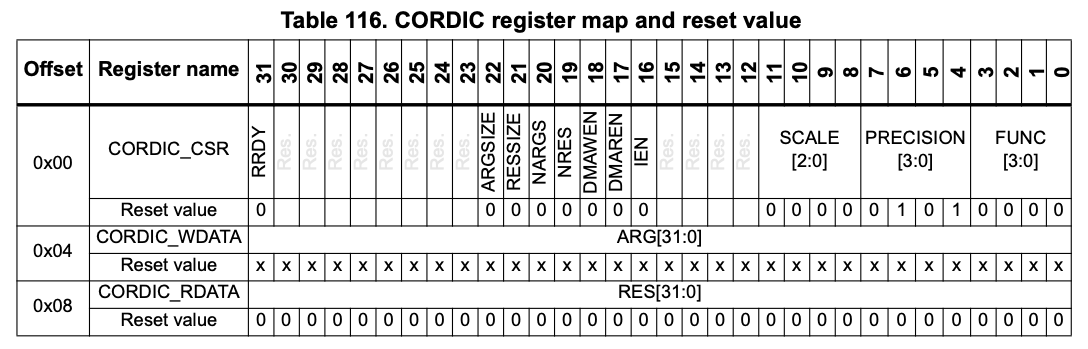

$RM0440 17.4.4

So there are three registers, just looking at this map it seems pretty clear that the first

register CSR is some kinid of configuration register, WDATA holds an ARG so that’s probably

where we Write our arguments, and RDATA holds a RES so it is probably where we Read

computation results.

Let’s break down the function of each property of the CSR register.

RRDY

This bit indicates if a result is pending in the output register RDATA.

It’s set and cleared by hardware, and can be used by software to determine if results are ready to be read.

ARGSIZE

The Cordic co-processor supports two data types:

- q1.31

- q1.15

These are fixed-point types, meaning the decimal point is at a fixed bit position. In this case, there is one bit to indicate sign, and 31 or 15 bits representing fractional components. Both of these types occupy 32 and 16 bits respectively.

So this bit is how the software controls the data type to be used for function arguments.

RESSIZE

Just like ARGSIZE, this bit controls the data type to be used for function results.

NARGS

Since there are different data types of different sizes, and different functions with differing input counts, the peripheral can accept a configurable number of writes to the argument register.

Consider a function like atan2 which has an $x$ and $y$ input. If we also select

the q1.31 datatype, clearly these two arguments will not fit in the WDATA register

which has a width of 32 bits.

In this case, we would need to write the arguments successively. The CORDIC must be

configured to accept this, with this (NARGS) register.

NRES

Just like NARGS, the number of reads from the RDATA register to be considered

a complete read of the function results, is configured with this bit.

IEN

The Cordic is capable of generating interrupts upon evaluation completion.

Whether or not it should is configured with this bit.

SCALE

Some functions benefit from having a software configurable scaling factor applied to the function arguments.

This bitfield represents $n$, resulting in a scaling factor of $2^{-n}$.

PRECISION

The Cordic algorithm is iterative, we can configure the number of iterations with this bitfield.

FUNC

Lastly, this bitfield allows us to select which function we want performed by the peripheral.

Nice, these are some pretty simple properties to configure.

Direct Registers

Let’s use the stm32-pac (peripheral access crate) to try configuring the Cordic.

fn configure_cordic(rb: stm32::cordic::CORDIC) {

// ...

}

Imagine we are in a scope where the PAC-level resource is accessible.

We can access the CSR register with a RegisterBlock writer:

fn configure_cordic(rb: stm32::cordic::CORDIC) {

rb.csr.write(|w| {

// ...

});

}

Fortunately for us, the SVD1 files provide us with register names, bitfields, enums, etc.

Let’s try configuring the function:

fn configure_cordic(rb: stm32::cordic::CORDIC) {

rb.csr.write(|w| w.func().sine());

}

How does that work? Rust already knows how to use the Cordic?

Kind of!

The PAC does provide a very useful direct interface to the register bitfields.

It does not, however, enforce or represent any behavioral logic. It’s just a nice interface for reading from and writing to registers.

But this is a good starting point, here’s an example of why this isn’t good enough:

fn configure_cordic(rb: stm32::cordic::CORDIC) {

rb.csr.write(|w| {

w.argsize().bits16();

.ressize().bits32();

.nargs().num2();

.nres().num1();

.func().sine();

.scale().bits(0);

unsafe { w.precision().bits(15) }

});

}

This is a full configuration of the peripheral. Looks fine doesn’t it. It certainly compiles.

Can you see the problem?

The problem is we set ARGSIZE to bits16 and NARGS to num2. In English,

we told the Cordic to expect two register writes of q1.15 arguments… which is impossible.

Two q1.15 arguments are supposed to be stored in a single word and written once.

So we put the peripheral in an invalid state and had no idea!

Here’s an even worse scenario:

fn configure_cordic(rb: stm32::cordic::CORDIC) {

// configured in some way...

}

fn use_cordic(rb: stm32::cordic::CORDIC) {

rb.wdata.write(|w| w.arg().bits(0x7000));

let result = rb.rdata.read().res().bits();

}

The peripheral was configured at some point, and we are trying to use it later to evaluate our arguments.

What is the value of result?

It’s a trick question!

Nothing about the type of rb indicates to us how the Cordic was configured.

Does it expect two register writes? What data type was it configured to? What function is it going to run?

Yeah… this is bad…

So how can we do better?

How can we leverage Rust’s type system to represent these configurations and enforce valildity?

Type-States

Let’s outline some fundamental ideas to get us started.

State

We will create types which directly correspond to specific hardware states called type-states.

Usually the hardware states will be in the form of register bitfields.

Type-states will implement a trait that looks like this:

trait State {

const RAW: Raw;

fn set(binding: Binding) -> Self;

}

The const RAW will hold the type-states bitfield value.

The function set will accept a binding that provides write access

to the appropriate bitfield, and return the type-state.

The latter aspect is important because if instances of type-states can only exist when the hardware is configured to represent them, we can make any process or type own the type-states it requires, for compile-time enforcement.

Let’s implement our type-states now:

ArgSize/ResSize

The first bitfields of the Cordic control register are for the argument and result size (type).

Recall, there are two possible types: q1.31 or q1.15. We can create types to represent this:

/// q1.15 fixed point number.

pub struct Q15;

/// q1.31 fixed point number.

pub struct Q31;

Really, we should use types from the fixed crate for the interfaces we will create, but

to avoid massive type signature cluttering, we can use the above types as Tags for the actual

fixed types:

/// Extension trait for fixed point types.

trait Ext: Fixed {

/// Tag representing this type.

type Tag: Tag<Repr = Self>;

}

/// Trait for tags to represent Cordic argument or result data.

trait Tag {

/// Internal fixed point representation.

type Repr: Ext<Tag = Self>;

}

…and implement them:

impl Ext for I1F15 {

type Tag = Q15;

}

impl Ext for I1F31 {

type Tag = Q31;

}

impl Tag for Q15 {

type Repr = I1F15;

}

impl Tag for Q31 {

type Repr = I1F31;

}

I1F15andI1F31come fromfixed.

Now, we can create the type-state traits for the Q15 and Q31 types:

mod arg {

type Raw = csr::ARGSIZE;

/// Trait for argument type-states.

trait State: Tag {

const RAW: Raw;

fn set(w: csr::ARGSIZE_W<csr::CSRrs>) -> Self;

}

}

mod res {

type Raw = csr::RESSIZE;

/// Trait for result type-states.

trait State: Tag {

const RAW: Raw;

fn set(w: csr::RESSIZE_W<csr::CSRrs>) -> Self;

}

}

…and implement them (with macros):

macro_rules! impls {

( $( ($NAME:ty, $RAW:ident) $(,)? )+ ) => {

$(

impl State for $NAME {

const RAW: Raw = Raw::$RAW;

fn set(w: csr::ARGSIZE_W<csr::CSRrs>) -> Self {

w.variant(Self::RAW);

Self

}

}

)+

};

}

impls! {

(Q31, Bits32),

(Q15, Bits16),

}

The result macro is very similar.

NArgs/NRes

The next bitfields configure the number of register reads/writes expected.

This is a little more complicated, because the value of these type-states is dependent on others.

For example, if two arguments are to be written of the q1.15 format, only one register write is needed. But if the data type is q1.31, two register writes are needed.

So some kind of “data count” and “data type” information is needed to determine the number of register interactions.

We have “data type” done, let’s add “data count” types to our system.

These won’t be type-states, as there is no hardware configuration pertaining

to number of values to be passed. So rather than making a State trait,

we’ll call this a Property:

enum Count {

One,

Two,

}

struct One;

struct Two;

trait Property {

const COUNT: Count;

}

impl Property for One {

const COUNT: Count = Count::One;

}

impl Property for Two {

const COUNT: Count = Count::Two;

}

Similarly to how type-states hold a

RAWconst, this property holds aCOUNTconst to indicate which count it is statically.

With this, we can create our type-states for register interactions:

struct NReg<T, Count>

where

T: types::Tag,

Count: data_count::Property

{

_t: PhantomData<T>,

_count: PhantomData<Count>,

}

Let’s look at the State trait for nargs:

trait State {

fn set(w: csr::NARGS_W<csr::CSRrs>) -> Self;

}

…and implement it:

impl<Arg, Count> State for NReg<Arg, Count>

where

Arg: types::arg::State,

Count: data_count::Property,

{

fn set(w: csr::NARGS_W<csr::CSRrs>) -> Self {

w.variant(

const {

match (Arg::RAW, Count::COUNT) {

// two registers are needed *only* with two arguments and Q31 size.

(types::arg::Raw::Bits32, data_count::Count::Two) => Raw::Num2,

(_, _) => Raw::Num1,

}

},

);

Self {

_t: PhantomData,

_count: PhantomData,

}

}

}

The implementation for results is very similar.

The body of set looks like it has runtime branching, but it actually doesn’t.

The branching logic is based on associated type constants, so the compiler knows the correct branch

based on the type. An inline const is used to explicitly show that this is the case.

Scale/Precision/Func

These type-states are trivial and follow the same design procedure as the previous.

Features

Sometimes, the states of a peripheral are too low-level to be meaningfully used one-by-one, as they work together to fascilitate a feature of the peripheral.

In the case of the Cordic, the NArgs, NRes, Scale, and Func states are tightly coupled

and fascilitate conducting numerical operations. Certain functions only support certain scales,

the number of desired arguments/results of a function determines the number of register interactions.

To represent these relationships, let’s create a feature that enforces these relationships:

trait Feature {

// states

/// The required argument register writes.

type NArgs<Arg>

where

Arg: types::arg::State + types::Tag;

/// The required result register reads.

type NRes<Res>

where

Res: types::res::State + types::Tag;

/// The scale to be applied.

type Scale;

/// The function to evaluate.

type Func;

// properties

/// The number of arguments required.

type ArgCount;

/// The number of results produced.

type ResCount;

}

This feature holds states and properties.

To understand what exactly this feature means, here’s an example:

- Name: SinCos

- Argument: angle

- Results: sin(angle) and cos(angle)

- Data Size: q1.31

The register configuration that would support this is:

- NArgs: 1

- NRes: 2

- Scale: 0

- Func: Sine

Scale value given by $RM0440 17.3.2.

So, a type SinCos can be made to represent this operation, and can implement

Feature like so:

impl Feature for SinCos {

type NArgs<Arg> = NReg<Arg, Self::ArgCount>

where

Arg: types::arg::State + types::Tag;

type NRes<Res> = NReg<Arg, Self::ResCount>

where

Res: types::res::State + types::Tag;

type Scale = N0;

type Func = Sin;

type ArgCount = One;

type ResCount = Two;

}

This implementation covers all permutations of argument and result data type.

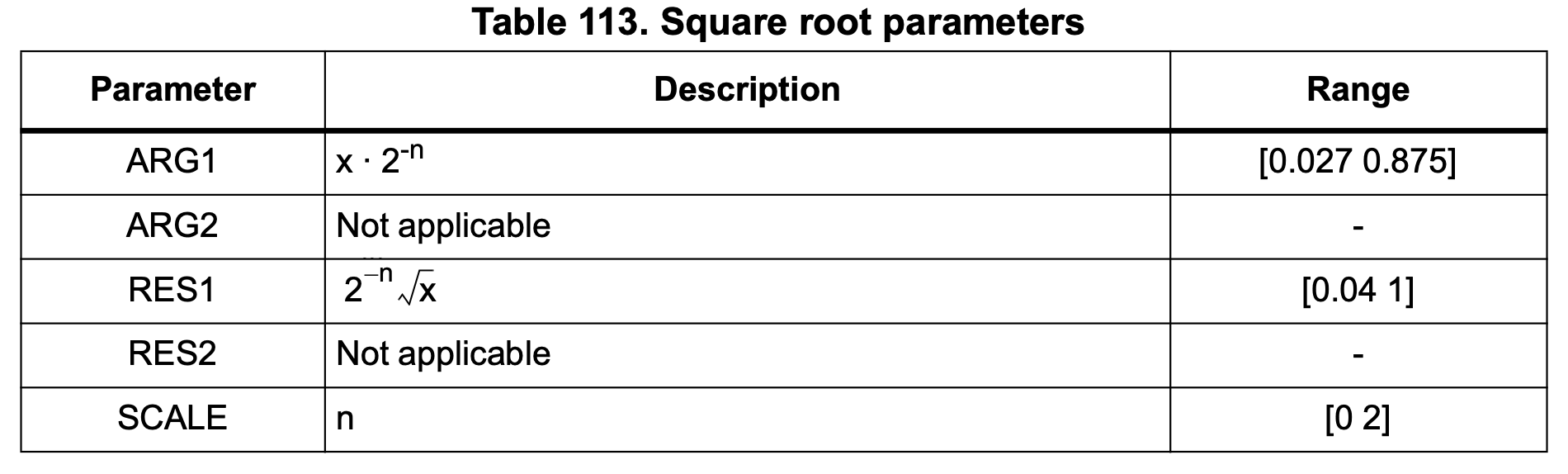

Unlike the Sin function, some functions have multiple valid scales.

For example, Sqrt:

$RM0440 17.3.2

As such, this feature type has a generic Scale. It will only be implemented for

valid scales, of course:

/// Square root of x.

///

/// This function can be scaled by 0-2.

pub struct Sqrt<Scale: scale::State> {

_scale: PhantomData<Scale>,

}

The implementations are fascilitated by some macros which are invoked like so:

impls! {

(Cos<N0>, One, One, Cos),

(Sin<N0>, One, One, Sin),

(SinCos<N0>, One, Two, Sin),

(CosM<N0>, Two, One, Cos),

(SinM<N0>, Two, One, Sin),

(SinCosM<N0>, Two, Two, Sin),

(ATan2<N0>, Two, One, ATan2),

(Magnitude<N0>, Two, One, Magnitude),

(ATan2Magnitude<N0>, Two, Two, ATan2),

(CosH<N1>, One, One, CosH),

(SinH<N1>, One, One, SinH),

(SinHCosH<N1>, One, Two, SinH),

(ATanH<N1>, One, One, ATan),

}

impls_multi_scale! {

(ATan<N0, N1, N2, N3, N4, N5, N6, N7>, One, One, ATan),

(Ln<N1, N2, N3, N4>, One, One, Ln),

(Sqrt<N0, N1, N2>, One, One, Sqrt),

}

Which implements Feature for the feature types with valid scales.

At this point, we have enough to begin creating our Cordic abstraction type.

First, let’s define a configuration. This type should hold all type-states:

/// Configuration for the Cordic.

struct Config<Arg, Res, NArgs, NRes, Scale, Prec, Func> {

arg: Arg,

res: Res,

nargs: NArgs,

nres: NRes,

scale: Scale,

prec: Prec,

func: Func,

}

It is important that the configuration owns the type-states, because that means all instances of

Configmust be valid, as type-state instances can only be created by calling theirsetmethod.

And our abstraction type:

/// Cordic co-processor interface.

pub struct Cordic<Arg, Res, Prec, Op>

where

Arg: types::arg::State,

Res: types::res::State,

Prec: prec::State,

Op: op::Feature,

{

rb: CORDIC,

config: Config<Arg, Res, Op::NArgs<Arg>, Op::NRes<Res>, Op::Scale, Prec, Op::Func>,

}

The Cordic type has less generic constraints than the Config type because the

Op feature encodes multiple states.

It is still guaranteed that all type-states are accounted for because the config is present, and per its definition, all type-states are present.

This definition also makes it clear that the NArgs and NRes type-states

are dependent on the Arg and Res type-states respectively via the passed

generic constraints.

Creation

It’s time to set up construction of our abstraction.

Firstly, let’s define the reset state of the Cordic.

This is a ubiquitous idea across HALs and peripherals, so we should represent

it as a trait in proto-hal:

/// Types that encapsulate a resource that can be configured to be

/// in a "reset" state implement this trait.

pub trait IntoReset {

/// The form of the implementor type in the "reset" state.

type Reset;

/// Transform the implementor type into the "reset" state.

fn into_reset(self) -> Self::Reset;

}

…and implement it:

/// $RM0440 17.4.1

pub type CordicReset = Cordic<types::Q31, types::Q31, prec::P20, op::Cos>;

impl<Arg, Res, Prec, Op> proto::IntoReset for Cordic<Arg, Res, Prec, Op>

where

Arg: types::arg::State,

Res: types::res::State,

Prec: prec::State,

Op: op::Feature,

{

type Reset = CordicReset;

fn into_reset(self) -> Self::Reset {

self.freeze()

}

}

And now, we can create an extension trait for the Cordic peripheral that allows it to be constrained by the abstraction type:

The idea behind constraining is that our abstraction operates within a state-space of our creation, effectively constraining the state of the peripheral to reside within that state-space.

/// Extension trait for constraining the Cordic peripheral.

pub trait Ext {

/// Constrain the Cordic peripheral.

fn constrain(self, rcc: &mut Rcc) -> CordicReset;

}

…and implement it:

impl Ext for CORDIC {

fn constrain(self, rcc: &mut Rcc) -> CordicReset {

rcc.rb.ahb1enr().modify(|_, w| {

w.cordicen().set_bit();

});

// SAFETY: we assume the resource is already

// in a reset state

// BONUS: this line enforces that the

// abstraction is of zero-size

unsafe { core::mem::transmute(()) }

}

}

The

transmutehas the wonderful side effect of compile-time validating that the abstraction is a ZST2 as we intend it to be.

Conversion

Now that the peripheral is constrained by the abstraction, we need a way to freeze the peripheral in desired states. This is how the peripheral is configured.

Let’s write a freeze method:

/// Configure the resource as dictated by the resulting

/// type-states. The produced binding represents

/// a frozen configuration, since it is represented

/// by types. A new binding will need to be made --

/// and the old binding invalidated -- in order to change

/// the configuration.

///

/// *Note: The configuration is inferred from context because

/// it is represented by generic type-states.*

pub fn freeze<NewArg, NewRes, NewPrec, NewOp>(self) -> Cordic<NewArg, NewRes, NewPrec, NewOp>

where

NewArg: types::arg::State,

NewRes: types::res::State,

NewPrec: prec::State,

NewOp: op::Feature,

NewOp::NArgs<NewArg>: reg_count::arg::State,

NewOp::NRes<NewRes>: reg_count::res::State,

NewOp::Scale: scale::State,

NewOp::Func: func::State,

{

use func::State as _;

use reg_count::arg::State as _;

use reg_count::res::State as _;

use scale::State as _;

let config = self.rb.csr().modify(|_, w| Config {

arg: NewArg::set(w.argsize()),

res: NewRes::set(w.ressize()),

nargs: NewOp::NArgs::set(w.nargs()),

nres: NewOp::NRes::set(w.nres()),

scale: NewOp::Scale::set(w.scale()),

prec: NewPrec::set(w.precision()),

func: NewOp::Func::set(w.func()),

});

Cordic {

rb: self.rb,

config,

}

}

RegisterBlock::write()is seen returning values here. This is not possible given the original implementation insvd2rust. I had to forksvd2rust, change the interface, and rebuild the PAC with the new interface.

This method is extremely robust. Removing any line will cause it to no longer be valid, and it will

not compile. If the type-states were not required to be owned by Config, there would be nothing

forcing set to be called on every type-state.

Operation

Now let’s set up actually running operations and getting results. We’ll start by creating an

Operation type:

/// An operation of the Cordic.

///

/// Enables writing and reading values

/// to and from the Cordic.

struct Operation<'a, Arg, Res, Op>

where

Arg: types::arg::State,

Res: types::res::State,

Op: Feature,

{

nargs: &'a Op::NArgs<Arg>,

nres: &'a Op::NRes<Res>,

scale: &'a Op::Scale,

func: &'a Op::Func,

}

This type ensures the appropriate type-states are set for an operation by borrowing them.

Let’s implement write and read methods.

impl<'a, Arg, Res, Op> Operation<'a, Arg, Res, Op>

where

Arg: types::arg::State,

Res: types::res::State,

Op: Feature,

{

/// Write arguments to the argument register.

fn write<Args>(&mut self, args: Args, reg: &crate::stm32::cordic::WDATA)

where

Arg: types::Tag,

Args: ?,

Op::ArgCount: data_count::Property<Arg>,

{

?

}

/// Read results from the result register.

fn read(

&mut self,

reg: &crate::stm32::cordic::RDATA,

) -> ?

where

Op::ResCount: data_count::Property<Res>,

{

?

}

}

Well we’ve run into an issue. The argument and return types are dependent on the operation. So how can we correctly design the function signature to accept and return those types?

Well, there can be either one or two arguments/results, we already created the data_count

properties to reflect that. Let’s make an extension trait for types which can be arguments or results:

mod signature {

/// The signature is a property of the operation type-state.

pub trait Property<T>

where

T: types::Ext, // arguments/results should be I1F15/I1F31

{

/// Write arguments to the argument register.

///

/// # Safety:

/// Cordic must be configured to expect the

/// correct number of register writes.

unsafe fn write(self, reg: &WData)

where

T::Tag: types::arg::State;

/// Read results from the result register.

///

/// # Safety:

/// Cordic must be configured to expect the

/// correct number of register reades.

unsafe fn read(reg: &RData) -> Self

where

T::Tag: types::res::State;

}

}

These functions are

unsafebecause their signatures do not support type-state validation.

…and implement it for a single value or tuple of two:

impl<T> Property<T> for T

where

T: types::Ext,

{

unsafe fn write(self, reg: &WData)

where

T::Tag: types::arg::State,

{

let data = match const { T::Tag::RAW } {

types::arg::Raw::Bits16 => {

// $RM0440 17.4.2

// since we are only using the lower half of the register,

// the Cordic **will** read the upper half if the function

// accepts two arguments, so we fill it with +1 as per the

// stated default.

self.to_register() | (0x7fff << 16)

}

types::arg::Raw::Bits32 => self.to_register(),

};

// SAFETY: all bits are valid

reg.write(|w| unsafe {

w.arg().bits(data);

});

}

unsafe fn read(reg: &RData) -> Self

where

T::Tag: types::res::State,

{

T::from_register(reg.read().res().bits())

}

}

impl<T> Property<T> for (T, T)

where

T: types::Ext,

{

unsafe fn write(self, reg: &WData)

where

T::Tag: types::arg::State,

{

let (primary, secondary) = self;

match const { T::Tag::RAW } {

types::arg::Raw::Bits16 => {

// $RM0440 17.4.2

// SAFETY: all bits are valid

reg.write(|w| unsafe {

w.arg()

.bits(primary.to_register() | (secondary.to_register() << 16));

});

}

types::arg::Raw::Bits32 => {

// SAFETY: all bits are valid

reg.write(|w| unsafe {

w.arg().bits(primary.to_register());

});

// SAFETY: all bits are valid

reg.write(|w| unsafe {

w.arg().bits(secondary.to_register());

});

}

};

}

unsafe fn read(reg: &RData) -> Self

where

T::Tag: types::res::State,

{

match const { T::Tag::RAW } {

types::res::Raw::Bits16 => {

let data = reg.read().res().bits();

// $RM0440 17.4.3

(

T::from_register(data & 0xffff),

T::from_register(data >> 16),

)

}

types::res::Raw::Bits32 => (

T::from_register(reg.read().res().bits()),

T::from_register(reg.read().res().bits()),

),

}

}

}

to_registerandfrom_registerwere added to thetypes::Exttrait for usage here.

Now the behavior for reading and writing arguments of different types and counts is defined.

Back to the Operation type, we can fill in the missing sections:

impl<'a, Arg, Res, Op> Operation<'a, Arg, Res, Op>

where

Arg: types::arg::State,

Res: types::res::State,

Op: Feature,

{

/// Write arguments to the argument register.

fn write<Args>(&mut self, args: Args, reg: &crate::stm32::cordic::WDATA)

where

Arg: types::Tag,

Args: signature::Property<Arg::Repr>,

Op::ArgCount: data_count::Property<Arg, Signature = Args>,

{

// SAFETY: Cordic is necessarily configured properly if

// an instance of `Operation` exists.

unsafe {

signature::Property::<Arg::Repr>::write(args, reg);

}

}

/// Read results from the result register.

fn read(

&mut self,

reg: &crate::stm32::cordic::RDATA,

) -> <Op::ResCount as data_count::Property<Res>>::Signature

where

Op::ResCount: data_count::Property<Res>,

{

// SAFETY: Cordic is necessarily configured properly if

// an instance of `Operation` exists.

unsafe { signature::Property::<Res::Repr>::read(reg) }

}

}

Once again, any error in the body of these methods results in compile-time errors.

Now we can implement start and result methods for Cordic

to allow users to run computations:

/// Start the configured operation.

pub fn start(&mut self, args: <Op::ArgCount as data_count::Property<Arg>>::Signature)

where

Op::ArgCount: data_count::Property<Arg>,

{

let config = &self.config;

let mut op = Operation::<Arg, Res, Op> {

nargs: &config.nargs,

nres: &config.nres,

scale: &config.scale,

func: &config.func,

};

op.write(args, self.rb.wdata());

}

/// Get the result of an operation.

pub fn result(&mut self) -> <Op::ResCount as data_count::Property<Res>>::Signature

where

Op::ResCount: data_count::Property<Res>,

{

let config = &self.config;

let mut op = Operation::<Arg, Res, Op> {

nargs: &config.nargs,

nres: &config.nres,

scale: &config.scale,

func: &config.func,

};

op.read(self.rb.rdata())

}

Dynamic Operation

What if the user doesn’t want to compute a static operation?

As it is now, the operation performed is fixed, as it is tracked as a type-state of the peripheral.

It is conceivable, however, that one may want to quickly change between multiple operations on the fly.

It would be quite unergonomic to have to re-freeze the peripheral into a new binding every time,

so let’s add a new operation feature implementation: Any:

/// Any operation can be invoked with this type-state.

pub struct Any;

impl Feature for Any {

type NArgs<Arg> = ()

where

Arg: types::arg::State + types::Tag;

type NRes<Res> = ()

where

Res: types::res::State + types::Tag;

type Scale = ();

type Func = ();

type ArgCount = ();

type ResCount = ();

}

Since Any’s implementation of Feature assigns the unit type to everything, a Cordic with

an Any as the Op generic will not satisfy the constraints required for start and result.

This is good as those methods no longer contextually make sense for a Cordic with an

unspecified operation.

So we need to implement a new way to conduct operations with the Cordic dynamically.

Let’s make a new trait for this dynamic mode:

/// A Cordic in dynamic mode.

pub trait Mode<Arg, Res>

where

Arg: types::arg::State,

Res: types::res::State,

{

/// Run an operation with provided arguments and get the result.

///

/// *Note: This employs the polling strategy.

/// For less overhead, use static operations.*

fn run<Op>(

&mut self,

args: <Op::ArgCount as data_count::Property<Arg>>::Signature,

) -> <Op::ResCount as data_count::Property<Res>>::Signature

where

Op: Feature,

Op::NArgs<Arg>: reg_count::arg::State,

Op::NRes<Res>: reg_count::res::State,

Op::Scale: scale::State,

Op::Func: func::State,

Op::ArgCount: data_count::Property<Arg>,

Op::ResCount: data_count::Property<Res>;

}

Now, the Op generic is passed in the run signature, rather than the Cordic

signature. So it can change over time.

The implementation is effectively the merge of start and result:

impl<Arg, Res, Prec> Mode<Arg, Res> for Cordic<Arg, Res, Prec, Any>

where

Arg: types::arg::State,

Res: types::res::State,

Prec: prec::State,

{

fn run<Op>(

&mut self,

args: <Op::ArgCount as data_count::Property<Arg>>::Signature,

) -> <Op::ResCount as data_count::Property<Res>>::Signature

where

Op: Feature,

Op::NArgs<Arg>: reg_count::arg::State,

Op::NRes<Res>: reg_count::res::State,

Op::Scale: scale::State,

Op::Func: func::State,

Op::ArgCount: data_count::Property<Arg>,

Op::ResCount: data_count::Property<Res>,

{

use func::State as _;

use reg_count::{arg::State as _, res::State as _};

use scale::State as _;

let (nargs, nres, scale, func) = self.rb.csr().modify(|_, w| {

(

Op::NArgs::set(w.nargs()),

Op::NRes::set(w.nres()),

Op::Scale::set(w.scale()),

Op::Func::set(w.func()),

)

});

let mut op = Operation::<Arg, Res, Op> {

nargs: &nargs,

nres: &nres,

scale: &scale,

func: &func,

};

op.write(args, self.rb.wdata());

self.when_ready(|cordic| op.read(cordic.rb.rdata()))

}

}

Cordic::when_readyis provided as a convenience. It polls the peripheral checking for theRRDYflag and calls the passed closure once the flag is set.

Now, Cordic<_, _, _, Any> types can call run!

Let’s add a conversion method:

/// Convert into a Cordic interface that supports

/// runtime function selection.

pub fn into_dynamic(self) -> Cordic<Arg, Res, Prec, op::dynamic::Any> {

Cordic {

rb: self.rb,

config: Config {

arg: self.config.arg,

res: self.config.res,

nargs: (),

nres: (),

scale: (),

prec: self.config.prec,

func: (),

},

}

}

Naturally, we can see exactly which type-states are no longer tracked when operating dynamically.

We don’t need to re-implement freeze for dynamic Cordics because

there are no generic constraints for the members of Feature for the

freeze impl block, neat!

Usage

Let’s see all our hard work in action, here is a minimal example:

fn main() -> ! {

let dp = stm32::Peripherals::take().expect("cannot take peripherals");

let pwr = dp.PWR.constrain().freeze();

let mut rcc = dp.RCC.freeze(Config::hsi(), pwr);

let mut cordic = dp

.CORDIC

.constrain(&mut rcc)

.freeze::<Q15, Q31, P60, SinCos>(); // 16 bit arguments, 32 bit results, compute sine and cosine, 60 iterations

// static operation

cordic.start(I1F15::from_num(-0.25 /* -45 degreees */));

let (sin, cos) = cordic.result();

println!("sin: {}, cos: {}", sin.to_num::<f32>(), cos.to_num::<f32>());

// dynamic operation

let mut cordic = cordic.into_dynamic();

let sqrt = cordic.run::<Sqrt<N0>>(I1F15::from_num(0.25));

println!("sqrt: {}", sqrt.to_num::<f32>());

let magnitude = cordic.run::<Magnitude>((I1F15::from_num(0.25), I1F15::from_num(0.5)));

println!("magnitude: {}", magnitude.to_num::<f32>());

loop {}

}

This outputs:

<lvl> sin: -0.70708525, cos: 0.70708954

└─ cordic::__cortex_m_rt_main @ examples/cordic.rs:45

<lvl> sqrt: 0.49999928

└─ cordic::__cortex_m_rt_main @ examples/cordic.rs:52

<lvl> magnitude: 0.55902183

└─ cordic::__cortex_m_rt_main @ examples/cordic.rs:54

Validation

So… what if I tried to use Sqrt with a scale of N3?

error[E0277]: the trait bound `Sqrt<N3>: op::Feature` is not satisfied

--> examples/cordic.rs:51:23

|

51 | let sqrt = cordic.run::<Sqrt<N3>>(I1F15::from_num(0.25));

| ^^^ the trait `op::Feature` is not implemented for `Sqrt<N3>`

|

= help: the following other types implement trait `op::Feature`:

Sqrt<N0>

Sqrt<N1>

Sqrt<N2>

The moment we try to apply an invalid configuration to the peripheral with freeze() the compiler stops us!

Moreover, it happily suggests some alternative valid configurations.

We have coerced the compiler into recognizing and enforcing hardware invariances.

>>> [All HALs should do this] <<<

Performance

Let’s inspect the binary to see if the abstraction introduced any runtime costs.

Manual:

// to view ASM generated

#[no_mangle]

#[inline(never)]

fn cordic_init(rb: hal::stm32::CORDIC, rcc: &mut rcc::Rcc) -> TestCordic {

unsafe {

(*hal::stm32::RCC::ptr())

.ahb1enr

.modify(|_, w| w.cordicen().set_bit())

};

rb.csr.modify(|_, w| {

w.argsize().bits16();

w.ressize().bits32();

w.nargs().num1();

w.nres().num2();

w.func().sine();

w.scale().bits(0);

unsafe { w.precision().bits(15) }

});

unsafe { core::mem::transmute(()) }

}

Abstraction:

// to view ASM generated

#[no_mangle]

#[inline(never)]

fn cordic_init(rb: hal::stm32::CORDIC, rcc: &mut rcc::Rcc) -> TestCordic {

rb.constrain(rcc).freeze()

}

Resulting assembly:

movw r0, #0xc00

movw r2, #0xf800

movt r0, #0x4002

movt r2, #0xff87

ldr.w r1, [r0, #0x448]

orr r1, r1, #0x8

str.w r1, [r0, #0x448]

ldr r1, [r0]

ands r1, r2

orr r1, r1, #0x480000

orr r1, r1, #0xf1

str r1, [r0]

bx lr

Identical! Zero Cost Abstraction achieved!

Conclusion

Clearly the abstraction is highly performant and does not incur any runtime cost, while providing a robust interface with compile-time validation.

You may have noticed that I did not touch the DMA capability of the CORDIC peripheral, and did not include it in the abstraction. This is because I have not finalized my ideas for standardizing DMA interaction with resource interfaces. I do plan to comprehensively discuss this topic and my design choices for a future HAL implementation for the ADC.

-

SVD files describe the layout of a microcontroller and are provided by the manufacturer. Rust PACs are generated from these files. ↩︎

-

Zero-Size-Types (ZSTs) do not exist in memory as they have a size of 0. The compiler can use this knowledge to conduct inductive reasoning and determine flow statically and with zero overhead. ↩︎